In July 2021, a bloom at the north end of Cayuga Lake produced microcystin—a potent liver toxin—at concentrations more than 4,000 times the safe level for drinking water. The water in that stretch of lake, had anyone consumed it, could have caused acute liver damage. This was not an isolated incident. According to a recent report in the Journal of Environmental Management, the Finger Lakes region has become a hotspot for harmful algal blooms, accounting for 34 percent of all blooms reported statewide between 2020 and 2022.

The stakes could not be higher. Approximately one million people get their drinking water from the Finger Lakes, including residents of Syracuse, Rochester's suburbs, and Auburn. Skaneateles Lake, which supplies Syracuse, is one of only six unfiltered public drinking water sources in the country—a status that depends on maintaining exceptional water quality. The region's $3 billion tourism industry and internationally recognized wine trail depend on clean, healthy lakes.

What Are Harmful Algal Blooms?

Despite the common name "blue-green algae," the organisms responsible for most harmful algal blooms are actually bacteria. Cyanobacteria were historically classified with algae because they photosynthesize like plants, but modern analysis of their cell structure has reclassified them as bacteria—they lack the membrane-bound nucleus and organelles found in true algae. These ancient organisms have existed for at least 2.7 billion years, and under normal conditions they remain present in low numbers as part of the natural microbial community in lake ecosystems.

Problems arise when warm water, calm conditions, and abundant nutrients trigger explosive population growth. These blooms appear as green paint, pea soup, or floating mats. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, cyanobacteria thrive at temperatures above 77°F (25°C) and outcompete other organisms as waters warm.

The real danger lies in the toxins. Microcystins, the most common cyanotoxins in freshwater, are potent liver toxins that the EPA classifies as possible human carcinogens. Research from Cornell University's College of Veterinary Medicine warns that dogs are particularly vulnerable—exposure can be fatal within hours.

Photo: EPA / Public Domain

Photo: EPA / Public Domain

Why the Finger Lakes?

The primary driver of harmful algal blooms is phosphorus, an essential plant nutrient that acts as fertilizer for cyanobacteria when it enters waterways. According to the Seneca-Keuka Watershed Nine Element Plan, approved by the DEC, more than 70 percent of the phosphorus entering those watersheds originates from agricultural land. Research cited by Cornell Cooperative Extension indicates that roughly half of applied nitrogen fertilizer is taken up by crops; the rest runs off into streams that eventually reach the lakes.

Climate change is accelerating the problem. According to the EPA, cyanobacteria grow faster than competing algae at warmer temperatures and possess unique advantages: they can regulate their buoyancy to access nutrients in deeper water while photosynthesizing in warmer surface layers. Research published in Harmful Algae found that cyanobacterial growth rates increase with temperature faster than those of green algae. The New York State Climate Impacts Assessment identifies climate change as a key driver of HABs, noting that more frequent and intense storms flush nutrient-laden runoff into waterways in concentrated bursts.

The trend is unmistakable. Data from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation shows that reported HABs statewide increased from 58 in 2012 to 1,054 in 2022—an eighteen-fold increase in a decade. Cayuga Lake, the longest of the Finger Lakes at nearly 40 miles, leads the state in total bloom reports.

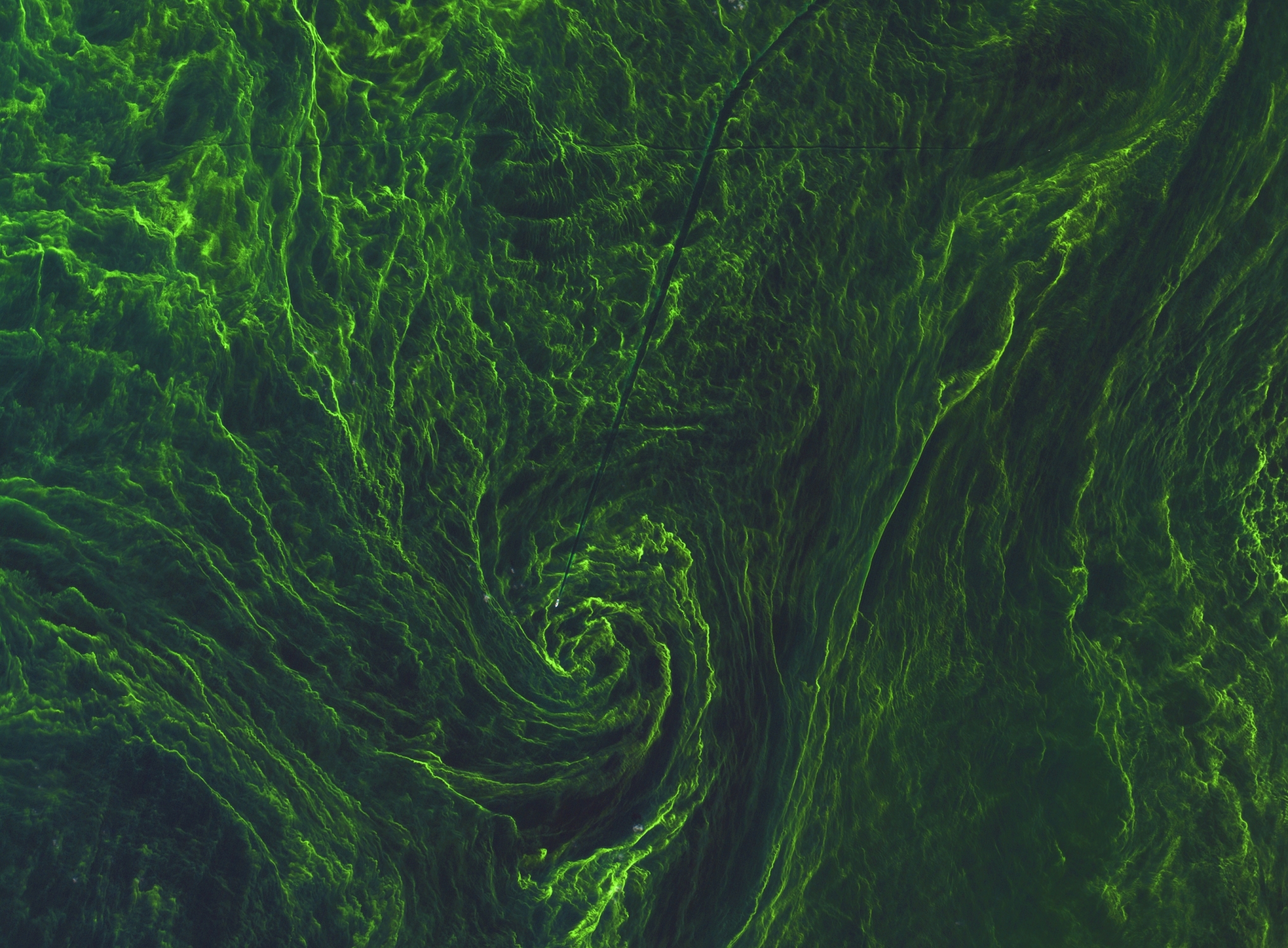

What makes this particularly challenging is a scientific paradox: several Finger Lakes are classified as oligotrophic, meaning they have relatively low nutrient levels compared to lakes that typically experience severe blooms. The USGS and DEC's Advanced Monitoring Pilot Project found that blooms in these low-nutrient systems are ephemeral and highly variable—they rarely appear in open water, instead concentrating along shorelines, in bays, and in coves. This is precisely where people swim, launch boats, and draw drinking water. The variability has required local researchers to develop new approaches combining advanced sensors, satellite imagery, and volunteer surveillance networks.

Photo: Medsker72 / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

Photo: Medsker72 / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

The Impacts

The threat to drinking water is not theoretical. In October 2018, the town of Rushville issued a drinking water advisory after toxins from a Canandaigua Lake bloom exceeded safe levels—residents were warned not to use tap water for drinking or food preparation. The City of Auburn has invested in carbon filtration specifically to remove cyanotoxins from water drawn from Owasco Lake. Syracuse's supply from Skaneateles Lake remains unfiltered; any significant bloom could jeopardize the city's exemption from federal filtration requirements, potentially requiring hundreds of millions of dollars in new treatment infrastructure.

The economic consequences extend beyond water treatment costs. Beach closures and advisory signs have become increasingly common during summer and early fall. The Finger Lakes wine industry contributes over $6.65 billion in economic impact statewide, and more than five million visitors travel to the region annually. The perception of polluted lakes threatens the tourism economy that many communities depend upon.

Wildlife and pets face immediate risks. Dogs are especially vulnerable because they drink from shorelines and lick contaminated water from their fur. According to Cornell's Riney Canine Health Center, cyanobacterial poisoning can cause seizures, liver failure, and death within hours. Fish kills and disrupted aquatic food webs also occur when blooms die off and decomposition depletes oxygen.

Photo: ESA/Copernicus Sentinel data / CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Photo: ESA/Copernicus Sentinel data / CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

The Response

New York State has committed significant resources to addressing the crisis. In 2024, Governor Kathy Hochul announced $42 million for the Eastern Finger Lakes Coalition of Soil and Water Conservation Districts to implement projects reducing nutrient runoff. That funding was disbursed to the Coalition in May 2025 and is now supporting on-farm and off-farm projects across the region. To date, the state has awarded more than $428 million in grants targeting phosphorus and nitrogen pollution.

The solutions focus heavily on agricultural practices, and local farmers are actively engaged in the effort. Farmers are implementing cover crops—planting winter wheat or rye on fields that would otherwise sit bare after harvest—to hold soil in place and absorb excess nutrients. The Nine Element Plan for Seneca and Keuka Lakes estimates that widespread cover crop adoption could reduce the total phosphorus load to those watersheds by 20 percent. Other practices include manure injection, which places nutrients directly into the soil rather than spreading them on the surface where rain can wash them away, and the establishment of vegetated buffer zones along streams to filter runoff before it reaches the lakes.

Scientific monitoring has become increasingly sophisticated. The USGS operates continuous water-quality monitoring stations on Owasco and Seneca Lakes, measuring temperature, dissolved oxygen, nutrients, and fluorescence signatures indicating cyanobacteria presence. The Seneca Lake Pure Waters Association coordinates a volunteer HABs Spotter network; in 2021, more than 120 trained volunteers monitored 60 miles of shoreline. Researchers are also testing new technologies, including handheld devices that can detect toxin-producing genes within hours rather than the days required for traditional laboratory analysis.

Photo: Andy Arthur / CC BY 2.0

Photo: Andy Arthur / CC BY 2.0

Protecting the Lakes

The most effective interventions operate at the watershed scale. Reducing phosphorus inputs requires sustained investment in agricultural best management practices, improved septic system maintenance, and upgrades to municipal wastewater treatment. The Total Maximum Daily Load analysis for Cayuga Lake targets a 30 percent reduction in phosphorus loading—a goal requiring continued collaboration between state agencies, local governments, farmers, and conservation organizations.

For those spending time near the lakes, awareness matters. The DEC maintains an online reporting system for suspected blooms and issues advisories when toxins are confirmed. The guidance during bloom events is straightforward: avoid contact with water that appears green or scummy; keep children and pets away from affected areas; never drink untreated lake water; and rinse immediately with clean water if exposure occurs.

The lakes remain vital—for drinking water, for recreation, for the economy, and for the quality of life that defines the region. The science is clear about what threatens them and what can protect them. The question is whether action can match the scale of a problem that climate change will only intensify.

For information on reporting suspected blooms or checking current advisories, visit the New York State DEC Harmful Algal Blooms page at dec.ny.gov. To support local conservation efforts, contact the Finger Lakes Land Trust, your county Soil and Water Conservation District, or lake associations including the Seneca Lake Pure Waters Association, Cayuga Lake Watershed Network, and Owasco Watershed Lake Association.