You've probably seen the photo. The stone bridge arching over a waterfall, mist rising through a narrow gorge, ferns clinging to layered rock walls that look almost too dramatic to be real. It's Rainbow Bridge at Watkins Glen State Park, and it's earned its place as one of the most photographed spots in New York State.

Here's the thing: the postcard doesn't lie. Watkins Glen really is that beautiful. The gorge descends 400 feet past 200-foot cliffs, threading 19 waterfalls into just two miles of trail. It's the most famous state park in the Finger Lakes, and deservedly so.

But there's a difference between visiting Watkins Glen and really experiencing it. The gorge holds layers that don't show up in photos—360 million years of geology, a Victorian-era tourist resort that once rivaled Niagara Falls in fame, a catastrophic flood that destroyed everything, and the Depression-era craftsmen who rebuilt it all by hand using native stone. Understanding those layers changes what you see when you walk through.

This guide gives you both: the practical information you need to plan your visit, and the stories that make those details meaningful.

What You're Actually Walking Through

The Finger Lakes themselves are the work of glaciers—massive ice sheets that carved eleven long, narrow valleys into the landscape as they advanced and retreated over millions of years. The most recent glaciation ended roughly 12,000 years ago, and when those glaciers melted, they left behind something geologists call "hanging valleys": tributary streams perched high above the newly deepened lake valleys, with nowhere to go but down.

Glen Creek was one of those streams. Left hanging above what would become Seneca Lake, the water had to descend hundreds of feet over a relatively short distance. That steep gradient created powerful erosion, and the creek has been cutting back into the hillside ever since—a process called headward erosion that's still happening today at every waterfall in the gorge.

The rock itself tells an even older story. The walls of Watkins Glen expose layers of shale, sandstone, and limestone laid down roughly 360 million years ago, when this part of New York was covered by a shallow inland sea. The Acadian Mountains—an ancient range that once stood where the Appalachians are now—were eroding into that sea, depositing layer after layer of sediment that eventually compressed into stone.

You can see this history in the cliff walls if you know what to look for. The horizontal bands are those ancient sea floor layers. The darker, crumbly rock is shale, formed from mud. The harder, blockier sections are sandstone, formed from sand. Because these rock types erode at different rates—shale faster, sandstone slower—the creek has carved a staircase effect: waterfalls form where hard sandstone caps softer shale, and plunge pools develop at the base of each drop.

At Watkins Glen, something unusual happened. The plunge pools formed so close together that their walls eventually eroded away, creating a sinuous, ribbon-like streambed unlike anywhere else in the region. The hourglass-shaped pools and curving rock formations are the result of millennia of water, sand, and gravity doing patient work.

Pay attention as you walk. The ripples preserved in some sandstone layers are ancient wave patterns. The smooth potholes scattered through the gorge mark spots where water and gravel swirled in the same place for centuries. And when you enter The Narrows—a section where the gorge walls close in and the temperature drops noticeably—you're stepping into a micro-climate, cool and damp, where ferns and mosses thrive in conditions that feel almost like a rainforest.

Then the gorge opens into Glen Cathedral, the widest and sunniest section, where the towering "cathedral wall" rises above you. The contrast is part of the experience: shadow and light, narrow and wide, the intimacy of the tunnels and the grandeur of the open spaces.

The Human Story

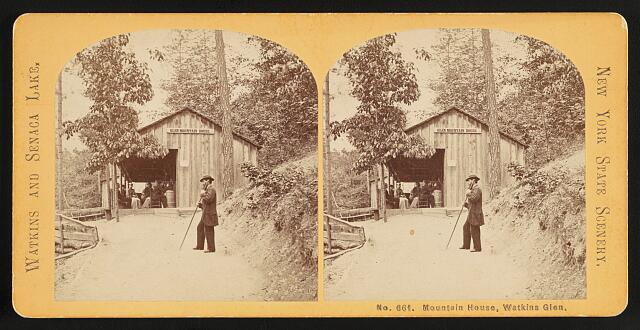

Photo: Glen Mountain House / NYPL Digital Collections / Public Domain

Photo: Glen Mountain House / NYPL Digital Collections / Public Domain

Before it was a park, this gorge was called Big Gully, and it was an industrial site. The water power was too valuable to ignore. By the early 1800s, a sawmill and gristmill operated at the base of the gorge—right where the parking lot sits today. Samuel Watkins, a New York City financier who'd purchased hundreds of thousands of acres in the region, invested heavily in developing the area. Workers built informal paths into the gorge to access the mills, and those paths became the first tourist routes.

The transformation from industrial site to destination began with a newspaper editor named Morvalden Ells. Originally from Vermont, he had been working in Elmira before moving to Watkins Glen in 1856, drawn by the gorge's beauty. Ells was a natural promoter, and he saw potential that went beyond lumber and flour. He partnered with Judge George Freer, who had inherited the property, and together they set about turning the gorge into a tourist attraction.

On July 4, 1863—in the middle of the Civil War—they opened "Freer's Glen: Mysterious Book of Nature" to the public. Admission was 25 cents. Ells had wooden stairs, bridges, and railings built to make the gorge navigable, and he named the various sections to help visitors remember (and talk about) what they'd seen. It was showmanship as much as conservation, and it worked. More than 10,000 tickets sold in the first year.

Over the following decades, Watkins Glen became a nationally known resort. The Glen Mountain House hotel opened in 1873. By 1902, the New York Central Railroad was selling Sunday excursion tickets directly from New York City. Mark Twain praised the gorge in his book Roughing It, writing that Rainbow Falls could "challenge the old world and the new to produce its peer" in scenic beauty.

By the turn of the century, a growing movement held that natural wonders like Watkins Glen should be publicly accessible rather than privately owned. In 1906, New York State purchased the property for $46,512, establishing it as a public park. The state replaced the aging wooden infrastructure with more durable materials—concrete paths and iron railings that were functional but decidedly industrial-looking against the natural stone.

Then came the flood.

On July 7-8, 1935, a massive storm dropped roughly 12 inches of rain on the area in just a few hours. Up in the gorge, debris and logs that had accumulated began to move. They jammed against the New York Central Railroad bridge that crossed high over the gorge, forming a dam. The water rose behind it—some accounts say nearly 100 feet—until the pressure became too great.

When the dam broke, a wall of water more than 20 feet high roared through the gorge and into the village below. It destroyed virtually everything in its path: the trail infrastructure, homes, businesses. The high school librarian, who had refused to leave her house despite warnings, was swept away and killed. The flood killed 43 people across the region and caused $40 million in damage.

For Watkins Glen State Park, it was total devastation. Every bridge, railing, and walkway in the gorge was gone.

But a Civilian Conservation Corps camp—one of the work camps President Roosevelt had established to employ young men during the Depression—had opened in the park just the day before the flood. Those young men, who had come to do conservation work, suddenly found themselves on disaster relief duty. And when the immediate crisis passed, they became the rebuilders.

Park designers saw the destruction as a strange blessing. The concrete and iron had never quite fit the landscape. Now they could start over. Instead of industrial materials, the CCC workers used native stone quarried from the site. They built low walls and arched bridges designed to blend with the gorge rather than impose upon it. The goal was harmony—construction that felt like it belonged.

The work took years. When it was finished in 1938, the result was the Watkins Glen you walk through today: stone staircases that curve with the terrain, tunnels that spiral through the rock, bridges that frame the waterfalls rather than block them. The CCC camp disbanded in 1941 when World War II began, but their craftsmanship remains.

When you walk through that entrance tunnel, when you cross Rainbow Bridge, when you climb the stone steps of Jacob's Ladder—you're walking on work done by hand during the Great Depression, by young men who turned a disaster into something that has welcomed millions of visitors since.

The Trails

The Gorge Trail

This is the main event. The Gorge Trail runs 1.5 miles from the Main Entrance (in downtown Watkins Glen) to the Upper Entrance, climbing approximately 400 feet along the way via more than 800 stone steps. It's open from mid-May through late October, with exact dates varying based on weather and conditions—check the park website before visiting.

A few key things to know: pets are not allowed on the Gorge Trail (they are permitted on the rim trails). There are no restrooms along the trail itself, only at the entrances. And the path is often wet from waterfall spray and natural seepage, so appropriate footwear matters.

The trail passes through a series of named landmarks, each with its own character:

The Entrance Tunnel spirals up through the cliff face, immediately separating you from the outside world. When you emerge into Glen Alpha, that first look up at the towering walls sets the tone for everything that follows.

Cavern Cascade, about 52 feet tall, is where you walk directly behind the waterfall. Expect to get misted—it's part of the experience.

The Narrows lives up to its name: the gorge walls close in, the light dims, and the temperature drops. Ferns and moss cover every surface.

Glen Cathedral is the opposite—wide, open, and sunny, with the dramatic cathedral wall rising above.

Central Cascade, at 60 feet, is the tallest waterfall in the park.

Rainbow Falls and Rainbow Bridge need no introduction. This is the photo spot. If you visit on a sunny afternoon, you may catch actual rainbows in the spray.

Finally, Jacob's Ladder—a long stone staircase that climbs to the Upper Entrance. Some visitors describe it as "butt-busting," and they're not wrong.

The Rim Trails

If the Gorge Trail is closed, too crowded, or you're traveling with a dog, the rim trails offer an alternative.

The Indian Trail (also called the North Rim Trail) runs about 1.1 miles along the northern edge of the gorge. It's forested and less dramatic than the Gorge Trail, but it offers several overlooks with views down into the gorge. Dogs are allowed on leash.

The South Rim Trail runs about 1.8 miles and connects to the larger Finger Lakes Trail system. It's more woodland walking than gorge viewing, but it provides access to the campground and pool area.

A suspension bridge connects the two rim trails, offering nice views into the gorge.

Both rim trails are open year-round, weather permitting.

Loop Options

You don't have to hike up and back down the Gorge Trail. Consider these alternatives:

Hike up the Gorge Trail to Mile Point Bridge, then return via the South Rim Trail. You'll see the most dramatic section of the gorge on the way up and get a different perspective (with fewer people) on the way down, while skipping the stairs of Jacob's Ladder.

For a longer day, combine all three trails into a 4.2-mile loop.

In summer, a shuttle runs between the Main Entrance and Upper Entrance (roughly $6 per adult). You can park at the top, shuttle down, and hike up—or vice versa.

Timing Your Visit

Watkins Glen draws over a million visitors annually. It's popular for good reason, but that popularity means timing matters.

The Crowd Reality

Some visitor reviews describe summer weekend mornings as quite crowded, with groups backed up at photo spots and the trail feeling more like a queue than a hike. The common advice to "arrive early" doesn't always work—many visitors report that everyone else had the same idea, and the parking lot fills by mid-morning on peak days.

What Actually Helps

Weekdays beat weekends significantly. If you have flexibility, a Tuesday or Wednesday visit will feel very different from a Saturday.

Late afternoon often works better than early morning. The last two to three hours before the park closes tend to be quieter, as day-trippers head home. The light can be beautiful, too.

Shoulder seasons offer the best balance. September after Labor Day through mid-October gives you fall foliage, comfortable temperatures, and noticeably smaller crowds. Late May and early June offer waterfalls at peak flow before the summer rush begins.

Consider walking against the flow. Most visitors start at the Main Entrance and hike up. If you park at the Upper Entrance and walk down, you'll be moving against traffic. Alternatively, do the Gorge Trail up and return via the South Rim for a different route with fewer people.

Staying overnight helps most. Campground guests can access the Gorge Trail at sunrise, before day visitors arrive. The park has 305 campsites (primitive, without electric or water hookups) and some rustic cabins available—though both book up quickly, especially for fall weekends.

Current Construction Note

Through summer 2026, the main tunnel entrance and Sentry Bridge at the beginning of the Gorge Trail are closed for construction. The Gorge Trail is still accessible via the North Rim Trail at the Main Entrance, the South Entrance, or the Upper Entrance. Check the park website for current conditions before your visit.

Planning Your Visit

The Basics

Parking costs $10 per vehicle. Your receipt is valid at other Finger Lakes state parks the same day, so you can visit multiple parks without paying again.

Restrooms are available at all three entrances—Main, South, and Upper—but there are no facilities along the Gorge Trail itself.

The swimming pool at the South Entrance area is Olympic-sized and open during summer months.

Camping is available at 305 sites. The sites are primitive (no electric or water hookups), but the campground has showers and comfort stations.

What to Bring

Sturdy shoes with good tread. The stone paths are frequently wet from spray and seepage. Hiking shoes or trail runners work well; sandals and flip-flops don't.

Water. There are no fountains along the trail, and climbing 800 steps in humid conditions will make you thirsty.

A light layer. The gorge is noticeably cooler than the surrounding area, especially in The Narrows.

Camera protection if you care about your equipment. You will get misted at Cavern Cascade.

While You're in the Area

Seneca Lake is right there—swimming, fishing, and boat access are available in the village.

Catherine Creek, just south of the village, is known for its spring rainbow trout run.

Watkins Glen International, the famous racetrack, is just outside town if motorsports interest you.

Downtown Watkins Glen is walkable from the park entrance and has restaurants, wine bars, and shops. The harbor area is pleasant for an evening stroll.

The Postcard and What's Behind It

That photo of Rainbow Bridge exists because the place really is that beautiful. The waterfall, the stone arch, the mist rising through green walls—none of that is exaggerated.

But now you know what you're looking at. The stone bridge was built by young men during the Great Depression, after a flood destroyed everything that came before. The rock walls are 360 million years old, layered sediment from an ancient sea. The gorge itself is only 12,000 years in the making, carved by a creek that's still cutting deeper every year.

Come for the waterfalls. Stay for the feeling of walking through deep time on trails built by hand. That's the Watkins Glen beyond the postcard—and it's worth the trip.